★ Themes ★ Form ★ Plot ★ Characters ★ Style ★

I love taking the time to stop and think about literature I read and movies I’ve seen and virtual worlds that I’ve explored. I love thinking about how profoundly different works have affected me. And it seems that there’s always something else to pick up when I take the time to reexplore them.

What Is Your Message?

★ What Is Your Story & Why?

★ Extrapolating and Intermeshing Core Ideas

★ Machinations Beneath The Surface

A Constructive Writing Process

Themes

★ Timeless and Universal Themes

Form

★ Setting and Breaking Expectations

★ Connecting the Dots

★ Sequels Break Coherence to Form

★ Formlessness

Plot

★ The Intersection of Form and Plot

★ Tropes

★ AI-driven Literature

Characters & Relationships

★ Three-Dimensional Characters

★ Pullbacks and Character Development

★ Anonymized Characters

★ Character Archetypes

Style

★ Literary Style

★ Temporality and Ordinality

★ Causality and Cardinality

★ Differential Style and Orthogonality

★ Cohesive Style

When Style Fuels Artistry

★ Birdman

★ Jackie Brown

★ Infinite Jest

★ The Crying of Lot 49

★ On the Road

★ Canterbury Tales

★ Ghost in the Shell

My Own Style

★ Style Experimentation

Why was it that these works affected me so much at that point in my life and how would they have affected me later on? When I first read that chapter or saw that scene, what was I thinking? What should I have noticed and why didn’t I notice it? What compelled me to finish that RPG, but not others? Was the story not as compelling or was the pace not consistent enough? Why was I so drawn to that character and how did my own thoughts about him/her change as the character developed? What was it that drew me in at first and why? If I was to create my own work, how could I recreate that magical moment?

Over time, your answers to questions like these will change as you learn more about life. So if you do not capture your reactions authentically and as they happen, you’re likely to lose touch with that part of yourself that you embodied at that time. This and other sweet zens are sure to follow.

What Is Your Message?

Do you ever feel like you’re carrying a message that no one else has heard? Do you feel the weight of that on your shoulders? Do you feel that if you didn’t write something down, that it might be months or years before you have the same thought? That it might be some time before anyone else is viewing a subject through that particular perspective? Perhaps, months, years or maybe never? … Though, obviously, not every thing I think of is revolutionary.

What Is Your Story & Why?

Do you feel that your experiences would allow you to craft a message that’s meaningful to people from all walks of life? How well do you really know people? Are there really “types” of people or is each person their own brilliant, perfect self? What makes them laugh, cry or come to understand something they couldn’t before? Better yet, what if your story allowed someone to understand things for the first time, that they had otherwise been missing out on? Some crucial aspect of life? Or something that perhaps everyone has missed in life.

Extrapolating and Intermeshing Core Ideas

How do you take a core idea and extrapolate it into a novel or script? I’ve found that this would be very challenging and the resulting material would seem stilted around one topic – it’d feel like a painting that just encapsulated one idea. Much more artistic is the painting that provides enough to stimulate exploration of a set of ideas. It’s not so straightforward that the art is … well, I’d rather not elaborate on every detail of these things.

The point is, you’ll be much more successful if you merge a few incomplete ideas. For some genres, content of mixed origination glued together roughly is perfect, as it adds a characteristic style to a work or a series of collaborations. The imperfections are what will lead to opportunities for improvement and thus creativity.

I hope to describe how to use elements and methods of this creative process to facilitate the development of higher-quality, more meaningful writing in myself, as well as my readers.

Machinations Beneath The Surface

Most people view things through a common lens because they haven’t dove in to explore their true nature. People who understand the inner workings or true nature of some tech, some medium, some idea, they see beyond the surface and into its mechanics. For them, this subject is marvelously more sophisticated, yet wondrously simple. It cannot be rigidly defined and neither can its potential. To them, it is difficult to state something is or is not possible because they see multifarious solutions.

It’s like peering over a bridge into a river, where some sections are deep and others are shallow, with rolling rapids and rocks exposed. But the deeper sections of the river, you can observe the rocks beneath the waves. Even though you can’t see the rocks or the riverbed directly, you can still infer their presence because of what you see on the surface. This is how I see reality; the divide between the physical world and the metaphysical. Some of the metaphysical must certainly be there, even though I can’t directly observe it. In fact, I may never see it, but I know that it’s there.

Boulder River

I get distracted because my mind is too populated with connections to random things. If my mind were a graph and whatever I was looking at or thinking of were our current node, then on average, I would have dozens as many edges to other nodes as the average normal person. Several factors contribute to this: I know tons of useless trivia, I tend to examine various trivial aspects of things and I try to correlate more than the average person.

And so I tend to pursue a lot of tangents and it’s a bit harder to control where my mind goes, but that’s actually a strength. If I rigidly focused my mind and ignored all the fleeting thoughts, there would be many roads never traveled. When I explored these roads, if I never wrote anything down, I’d never remember anything. And for the longest time, I didn’t.

A Constructive Writing Process

★ Themes ★ Form ★ Plot ★ Characters ★ Style ★

If I ever felt I had the time to write something meaningful, I imagine I’d use a kind of constructive process, involving the following: themes, style, characters, relationships, plot elements & form. Keep in mind that I’m keeping this focused on literature and that I also have mostly no idea what I’m talking about. Here, I’ll describe each type of constructive element and later, I’ll enumerate over some specific themes that interest me personally.

★ Themes ★

Of all the elements, the most important by far is theme. This is going to drive the internal dialogue of your readers and hopefully any external discussion they have as well. After all, art is much less so what it is in itself and more so the sum of what it inspires in us. There is no such thing as a “finished” work of art. And thus, works that don’t drive a dialogue and works that don’t make us ask new questions or provide a new light with which to revisit old modes of thinking: these works just don’t have as much depth. They are flat.

Timeless and Universal Themes

And for writing, the themes you choose and how you work with them, this determines the depth of your work. Some themes are more relevant to some than others. Some are played out, but might be fresh if you provide a new lens. There are many which seem relevant now, but whose importance will soon fade. These stories will likely vanish from the pages of time.

Thus, it’s important to choose timeless and universally relevant themes that everyone can value or appreciate. But what is universally relevant and what is timeless? As modern civilization continues to progress towards the unknown at an exponential rate, it seems that less and less would be timeless. Or maybe some works will acquire an air of timelessness as examples of the rapid development through the 21st century. Perhaps novelty is better preserved with exponential development.

A list of themes I would like to explore will be enumerated in part two.

Illustration from the 12th Century Eadwine Psalter

★ Form ★

What’s the overall form of the plot? This is a major dependency of all the elements. That is, changing the form will necessitate reworking many aspects of everything else.

Your story isn’t just the collection of facts from the plot. It’s so much more than that. It’s a journey that your readers will embark on and no reader will ever set out on the same journey. Readers will form very different interpretations of your work and you’ll find many readers whose reactions to elements of your work will cluster together. As the artist, it’s your task to understand how those various clusters will form and why. In other words, in what different ways will people react to the same scene or character and why?

Choosing the appropriate form can either make or break a work. The form is the story, as the reader or viewer experiences it. This needs to be well thought out and strategically applied to your work. By structuring the form of your work, you can magnify the reader’s emotional responses to some elements. Done well enough and you’ll find consumers want to re-experience your work, which is a far more accurate measure of validation and valuation than the score on their review, if they write one.

Setting and Breaking Expectations

Some plot elements can have a much more dramatic effect if some of the ending is revealed up to the reader up front – think Star Wars. This totally changes how a reader will experience your story. Instead of looking forward into the complete unknown, your reader knows the ending, or at least parts of it. There are these waypoints that must be connected sometime in the future. Having these kinds of waypoints will cause someone to be more invested in your story because their mind is going to constantly reevaluate how the stories current elements must connect to some events in the future.

Connecting the Dots

And so, their mind is always trying to connect the dots. This is just generally true with the human mind: it speciallizes in this. So give it some far off points to extrapolate to and it will kick our mind into high gear. In particular, it will engage the reader or the viewer’s imagination. And this is much more interesting to our subconscious mind, since it reconstructing the path from our current place in the plot to the future is a problem that is at least partially resolvable. That is, as opposed to just iteratively appending more plot details onto the existing storyline. There’s not much work there for the subconscious mind.

Also, there are more advanced examples of form used in the Star Wars trilogy, which is a ringed plot. It’s a trilogy of trilogies, began in the middle of a ringed story. The “ringed” form is well known in literature and Star Wars is like a meta-form of that.

Sequels Break Coherence to Form

Why is that that sequels don’t usually stand up to the first works? Often, it’s because the author didn’t have another direction planned for the work. The stories for the sequels feel “tacked on.” They seem isolated or self-contained or, worse, stilted in how they are interwoven into the original work. They might intertwine with the previous work well, but the previous work lacks the ability to intertwine as well with the sequel, depending on how the author left openings for sequels.

At the same time, it can sometimes be cheesy when there’s a bit written into the story and I immediately think “oh, I see, that’s where they want to make this a trilogy.” But that’s better than tacking on a self-contained sequel. Either way, the premise of subsequent work has changed the work itself. How does one construct a story without planning on the sequel? Sometimes, it’s best to travel hundreds of years in the past and explore some stories from a little known part of the mythology for the original work.

Another better way, which embodies a kind of formlessness, is to construct a story, adding in enough extraneous, unresolved material to leave openings for connected works. Done in the right way, this is a technique that can add to the complexity of the original work and the work should feel both homogenous and heterogenous. Think of one of those automatic, contextual photoshop brushes. How does it work? It checks the surrounding area and fills in the pixes so nothing stands out too much. This technique is a bit similar. And when you mixin enough extraneous heterogenous detail into your story, it feels natural. And when that’s not there, it feels constricted, just barebones plot.

Sequels can change the meaning of the first work. It’d be hard for Star Wars Episode VII to have quite the same effect as on someone who waited nearly thirty years from the release of Episode VI. I’m not at all saying there’s anything wrong with how JJ Abrams approached the sequels, but it’s impossible for that work to have the same effect as it did on people who grew up with the first six episodes.

Sometimes it’s best to leave the reader or viewer seething with unresolved tension. Other times, a story should begin and end. And that’s it. You’ve explored the world. Time for a new story. This is something I really like about anime and manga and I’ve written a post about it before in Lean, Kanban and Anime. There are the franchises that return again and again, but there are so many one off stories that last just a season or two. This gives the storytellers the chance to explore a set of characters and develop them without abandon. If a show is going to be short, significant characters can die or whatever. There’s less risk there and because of that, the stories can have more varied developments.

Formlessness

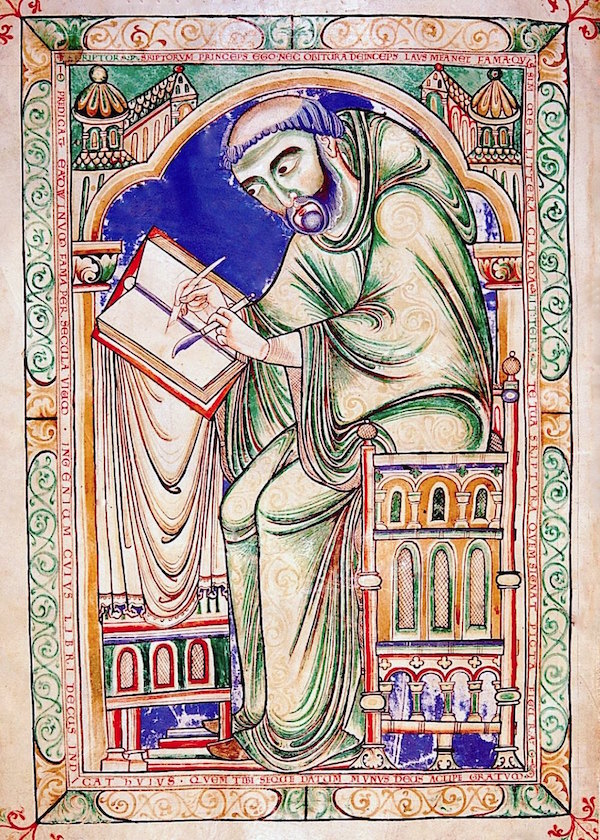

No Longer Human(1948) by Osamu Dazai is an excellent example of formlessness. I haven’t read it, but I’ve seen the anime based on it, which is part of Aoi Bungaku, a collection of japanese literature adapted to anime. It’s presumed to be partly based on the life of Osamu Dazai, who committed suicide shortly after publishing it. The anime follows the life of Oba Yozo after a disastrously failed double suicide attempt and delves into his childhood and his recovery from the failed suicide.

As for themes, it speaks powerfully about the role of the individual in relation to society. There are several brilliant role reversals woven into the work, especially towards the end, which are only made possible by the form of the novel. It’s difficult to see these coming, but they are pulled off just right and add a ton of depth to the characters in the story. Two of the characters are so similar, yet so distinctive. Neither really fits into society and both are kind of outcasts, but one is able to reconcile this, while the other makes a few majestic steps forward and several equally tragic falls backward.

Only having experienced the anime, I think the story seems formless because it’s partly based on the life of the author and thus, traditional form is right out the window. Usually, stories adapted from real events end up being shallow and one-sided. But here, elements of form are woven in on top of the pieces of the author’s life story, resulting in a very complex story about life with very real characters. The end of the anime feels almost like the climax of a chess game, where there are several pieces holding others in place and everything suddenly unfolds, leaving almost nothing remaining.

No Longer Human Manga

★ Plot ★

As you decide on major and minor themes, you should begin thinking of major and minor plot elements that would help you expose them.

The Intersection of Form and Plot

It’s the intersection of form and plot that allows for plausible alternate explanations to a storyline. Again, this is a priceless tool for getting your reader to engage and invest in your story. It’s going to cause them to reevaluate the characters, again and again. Placing your characters in situations where the character misunderstands them and makes mistakes and getting the reader to misevaluate the storyline: that is powerful storytelling that can cause the reader to reevaluate what they know of their own reality, as well as your fantasy. It’s especially important to look for form and plot that allow for plausible alternate explanations. So writers need to be capable of identifying duplicitous scenarious or portraying scenarious in such a way that allows for duplicitous explanations.

Tropes

There are generic kinds of events and events that are genericizeable which can allow a writer to enumerate reusable scenarios for minor plot events. And major plot twists as well. These are like tropes and using the same ones over and over can be a bit annoying. Yet, some tropes are incredibly useful for exploring specific themes, like betrayal. You might even say that a particular trope would be required for exploring some themes. In order to explore epic betrayal, you need a character that betrays another in an epic way. And to explore that to the full effect, you need minor events in your story that establish a trusting relationship between the two.

Category theory is great for kind of genericizing plot events or stories from real life. You can take some memories or stories you’ve heard and just abstract the characters or combinate & reapply the same “type” of scenario with different characters until you find something interesting. But being able to identify those kinds of compelling events and types of events from real life and from other stories is the skill here. What types of events would be most interesting when applied to different characters and situations.

AI-driven Literature

In terms of getting an AI algorithm to write literature or movies, one challenge is managing the interweaved web of dependencies between major/minor plot scenarios. And the big challenge is to get an algortihm to weave those events together for some higher purpose that allows the work to inspire in its readers a discussion about life itself.

There has been a ton of work put into this. AI has been trained on academic papers, political speeches and screenplays. AI even wrote this screenplay Sunscreen, which was produced and completed. There’s still a lot of work to be done. N-gram models are way too simple. Sequence-to-sequence is used in a lot of work with language, but that’s still not going to cut it.

For the next paragraph, just think: “Watson” retired from IBM and kicking our ass at jeopardy to write novels. And his memoirs. That’s basically all I’m saying.

Any neural network that doesn’t actually process the semantics in the language of the text into a model based on information and knowledge isn’t going to be able to do much. Most AI algorithms that process text and language rely on the frequency of words, but don’t venture too far into semantics. And what I’m thinking about is a network that takes the facts and information and plot movement contained in the semantics and then constructs a neural network based on that. It then mulls over clusters of higher-order data and produces something novel … which is punny if you think about it.

The best use for AI in writing for now is for the exploratory process: it’d be great at combinating through scenarios for characters, chaining them together and then passing control to screenwriters or focus groups or something. These higher-order events can be abstracted from the kind of knowledge and information that Watson aggregates. These higher-order events can be linked together. Just visualized one of those massive old-school synthesizers, with all the patch cords chaining various modules together.

Ergo Proxy

★ Characters & Relationships ★

Behind themes, your characters, their relationships and the development of both might be the most important parts. They will help you elucidate your themes. IMO, ideating all of this is some the hardest part of the creative process for literature and screenplays, besides the hard work of writing and editing a book or screen play. It’s all so ephemeral. It can shift so easily. What if you think you have a good story, but you get a few months into thinking it out … and it just doesn’t work?

Your characters must feel real in not just your mind, but in how they appear to others as well. Almost like an actor, you must be able to simulate their personality in your mind. And others should be able to as well. What would these characters do? How would they dress? Why? How does their appearance affect their behavior? Their position in their society and their personality, how does that contrast with the social norms of various strata? Why? Why is that important to painting the picture of your world? What is it that is going to resonate with readers and viewers? Why? What would make your readers and viewers want to cosplay this character? What is going to be controversial and are those controversial elements relateable?

Some characters, you will need to create as you need them for just one or two scenes, but that doesn’t mean they’re not worth investing energy into. Sometimes these characters are the best because you don’t have to worry about maintaining them and so you can contort their personality and traits a bit more for a bit of literary chiaroscuro.

What makes your characters real? What traits, mores and values do your fantasy realm’s people share that must be universal, with even our own world? And for every one of these questions: ask why! No, ask Five Why’s! By the way, Five Why’s is basically the application of pullbacks, which I’ll cover in just a second. The apparel that your character wears, what is its purpose to their world? Does form fit the function? Or is it just extraneous baggage? What hero wants to dress up every day with with crap that is mere baggage? Maybe there’s a story behind that ring or that leather piece? Who knows.

What is this character’s comfort zone? And what happens when they get harshly placed outside it? Do they react realistically? Do they change? What provokes their change? Or does the character, a high class princess that’s never seen a fleck of dirt, just magically adapt to circumstances she couldn’t psychologically tolerate? Because that wouldn’t be “realistic” which is a pretty fun term to toss around when referring to fantasy realms. Yet, you want to construct this realm in the mind of your viewer, so you want all the details to be coherent. You want them to construct this world in their mind because they want to escape our common reality, which is quite boring. So you owe it to them to flesh it out. On the other hand, you need to give yourself room for flexibility: don’t flesh out so many details if it’s going to be a problem to be stuck with them.

Three-Dimensional Characters

And so, to get “three-dimensional characters,” I’ll again return to category theory – this time to pullbacks. It’s more useful to let the reader construct their version of the character in their head because if you try to do it for them, it’s going to feel forced and stilted. Try to avoid describing the events and details at the surface.

So to sculpt these more authentic characters, you find that writers will mix one of two strategies. Both are necessary, though the first is much better IMO. First, they may strategically filter what is described at the surface and use that to allow you to imagine what must lie below. And secondly, they may attempt to directly describe the thoughts and inner feelings of the characters to articulate how a reader should perceive the surface details. This is necessary when you want to make sure that your reader is thinking about certain things when a scene is unfolding. It’s like putting text in bold. Sometimes you want to do that.

And you have to take the limitations of your medium into account. A movie only has a running time of 90 - 120 minutes, tops. You need to change how you develop your characters so you can do it faster, unless your character is already fairly well known, like a comic book superhero or something.

Pullbacks and Character Development

Try to refrain from techniques like expository dialogue, especially if you’re using it to expose emotional state! LOL, definitely don’t do that.

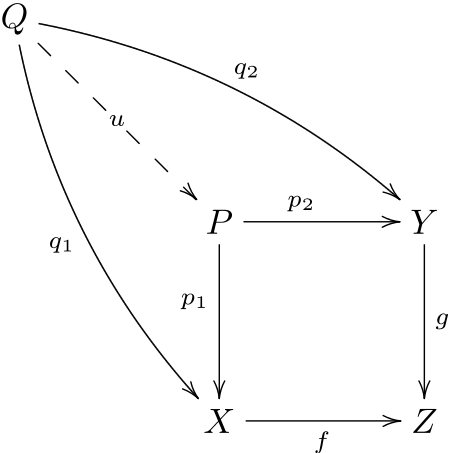

So, instead use the category theory concept of pullbacks. And please note, this concept doesn’t really map up one-to-one with the concept with category theory, but I think I can illustrate some important points about both by illustrating with this analogy. And yeh, it’s abstract non-sense mathematic mumbo jumbo, but I can break it down. You’ll see that it’s simple and relevant.

Pullback Diagram

So, P and Z are your reader’s perceptions of the character

Alice, before and after some character development. Lets say that

Z is your character after some transformative event that makes your

reader think Alice is greedy and shortsighted. To make the analogy

to category theory more clear (this isn’t really important) then P ->

X -> Z and P -> Y -> Z represent the transformations of greedy

and shortsighted, in either order. Whether or not you apply the

functions greedy or shortsighted first or second doesn’t matter,

you still reach a place Z where the reader perceives both are true

about Alice. But if you just do it this way, it’s the equivalent of

writing The character Alice is greedy and shortsighted. Boring,

right? But that is the goal. You need the reader to believe that

Alice is these things.

So a pullback is a transformation of P -> X -> Z and P -> Y -> Z

so that you can go from Q -> X -> Z or Q -> Y -> Z. And there is

the implied existence of a function u that transforms Q -> P. What

is important is that you have pulled back from the overly simple

statement The character Alice is greedy and shortsighted and

obfuscated that with a situation or event that allows the reader to

understand that. These pullbacks are also useful for genericizing

types of events and situations, so that they could be reapplied to

other characters.

And so, these kind of pullbacks are essential to writing literature in

such a way that allows the reader theirself to search for your

meaning. It makes it a bit harder, so that they spend more time and

energy trying to understand your art. These kinds of pullbacks also

make your art a bit ambiguous. It’s clear you wanted to spark a

dialogue on greed and myopia, but now your readers need to discuss

amongst themselves what you actually wanted to say. When truly, you

wanted them to explore these themes or character traits because they

are complex and the reason you thought about them enough to inspire

art in the first place is because there is no “right” answer. Art that

is so direct & obvious doesn’t inspire enough discussion and

investment of energy to last.

Anonymized Characters

There is a kind of merger of characters with the mathematic concept of type theory. Don’t freak out! Type theory is basically Mad Libs. That’s all. If you want to get fancy, think Mad Libs with tree-like data structures.

Type theory sounds overly abstract, but it’s applicable to writing and the creative process. Type theory can be applied to both the situations you’re character will be in as well as to the characters themselves. It allows you to compare and specify parallels between the structures of data, in this case characters and events. In computer science, type theory is very useful for functional programming. If you were to model literature you would find yourself discovering a ton of connections to category theory, as we already have.

For the situations you want to use to highlight your chosen themes, you’re going to need characters to fill various roles. If your characters are pulling off a heist and one of them gets left behind, it could be any of them, but why should you pick each one? The role is the character that needs to be left behind, which is necessary for some future element of the plot. If your characters pull off a series of heists, there might be similar features shared between all of them: specific events or roles for a character to fulfill.

So, if you’ve enumerated these generic situations and plot movements that you want to use to construct your plot, then you can also create anonymized characters to attach to specific situations. This way, you can evaluate characters for that role in that situation to find the best fit. Changing characters that are part of a scene can have ramifications on dependencies to the story. E.G. the character that gets left behind in the heist was originally supposed to be in a scene just a bit later on, but now that’s a plot hole and a dependency issue to be resolved.

But anonimyzing the characters that are part of your scenes allows you to be a bit more flexible with your story. Because the imposition limitations often sparks creativity, then by evaluating which characters make the most sense for each scene and resolving the dependency issues that arise by creating explanatory scenes, you’re actually augmenting your creative capacity. I’ve always found that imposed limitations cause me to be much more creative than usual.

And so, if you have these anonimyzed characters, you might specify some of their actions and reactions in specific scenes, but because you haven’t decided their identity, you can always merge them with other characters to some extent. E.G. well for scene A, we need a heroic character that can rappel onto a balcony to save the day and that matches up with character B.

Character Archetypes

Ahhh the tsundere. Who doesn’t love a good tsundere? Anime shows often seem to have one. It’s the character, usually a girl, who acts like she doesn’t approve of our unlikely hero. She remains cold and distant, but why?! And gradually they grow close after the hero proves himself in some way.

These character archetypes are all over the place. There’s the distant mystic. The thief with a heart of gold. The homeless guy who’s seen everything. The evil stepmom. The unlikely hero. The valiant prince. The trickster. They’re all over literature and it’s nearly impossible to create characters that break these molds. You have to be familiar with them because you’re inevitably going to copy traits from them whether you know it or not. You can try to combine one or more archetypes, but that’s not such a great approach. A good idea would be to practice creating characters that embody these archetypes in some way. If you can master that, then you should know how to create characters that differ from them in some significant way.

Greek mythology and other ancient traditions are a great source of stories about characters that seem to best embody these archetypes. And I wonder: is that because they are the most pure implementations of these archetypes? Or is it because they were some of the first and everything is based on them?

The Icarus Archetype

Ergo Proxy’s Monad Proxy

★ Style ★

Cultures have evolved over time, as have people and the personality types and metatypes they embody. So has literature; myths have evolved and so has the way we tell them. Storytellers have found that one of the best ways to change a story is to change how they present the narrative to the reader, the listener, the viewer.

New technologies open up new ways of telling old stories. Higher bandwidth, instantaneous communication has given us the flat world of modernization, where everyone and every culture is essentially on the same playing field. Or rather, we seem to be eternally moving in that direction. The total quantity of information that is shared between the entire world has never been higher and so we have also changed the way we share information.

Further, this society urges the individual to stand out. So in that regard, modernization has encouraged writers to be creative in how they tell stories. The turn of the 20th century gave us stream of consciousness for example. People were in the middle of the intellectual and cultural revolution that would pave the way for the technological and philosophical developments of the 20th century. We were beginning to understand then mind, body and world like never before. The variety of writing styles that were put into publication underscore this and reflect the liberalization of control over publication.

So How About That Modernization, Eh?

Literary Style

So what is literary style? Style seems to mesh together the other literary elements. Style evolves over time and follows trends. Style is how a writer chooses to tell a story. Experienced writers will consciously embed elements of style throughout their work’s creation. They might have developed their own distinctive style, but they wouldn’t tell you that. That limits other people’s scope of perspectives, when looking at their work.

Literary style includes the language an author chose to use. That vocabulary includes cultural connections and evokes imagery, so style includes that imagery inspired by the use of language. It includes the overall format of the work. The author has a choice over the level of clarity they provide and what they choose to focus on. The narration can vary per chapter or per character as well, so that focus or perspective can change over a work. Some authors and works rely on a lot of wordplay. This is difficult to pull off well and those connections can be lost over time.

Style includes how an author chooses to develop their characters and the level of parallelism and connectedness in their characters. In other words, the form an author uses or the themes they explore are best highlighted when there is a connection between movements in character development.

Temporality and Ordinality

Some works employ a kind of temporal variation, a distortion of time in where events or the experience thereof can shift with respect to time. Ordinal variation refers to variation in order itself. In fact, every book employs temporal and ordinal variation to some degree because there is no sense of time in words on paper. They are just words on paper, chapters in a book. There is no time there. The only sense of time arises from how a reader explores the pages in the book. The reader provides that sense of time by consuming the work. Authors need to be well aware of how it feels to read their own work. Thinking about other people actually reading your writing sparks motivation to write differently. I don’t want to change my art for others, but it’d be a lot cooler if others enjoyed consuming it.

Causality and Cardinality

Another similar techniques employ variation in cardinality and causality. Distorting cardinality requires distorting how people perceive a collection of literature or the ideas in a book by changing the sets of ideas that people group together. We see this a lot with reboots: people want the franchise to be rebooted, so they can relive the myths they love as though they were new again. Just a little bit of this is great. Just a little bit. Too much rockin’ of the foundations is a bad thing. This style of cardinal distortion can be contained to a single work.

And by distorting causality, some seriously cool Dr. Strange ish becomes possible. In other words, by breaking logic or altering the structure of ideas brought to life by words, new possibilities are available. This aspect of Virtual Reality excites me. No, it is not the simulation of reality that stimulates my imagination. It is that the very foundations of reality can be broken and a coherent world can be made and consumed viscerally. The rules of physics can be remade. And this can be done with fiction, writing and cinema as well. This is what frustrates me about first person shooters and other overly realistic video games. Why would you want to escape to a simulated version of reality that almost exactly mirrors the version of reality that you know?

One place where you see causality broken is the Legend of Zelda. I stopped bothering trying to figure that plot out around Windwaker. LMAO. But the truth is – or my personal take on the series – it’s a legend. What you are playing through is not a single epic saga. You are experiencing the story as a legend. You are living it as it is told and retold. And that is so awesome. It’s also very freeing in that the series of the Legend of Zelda can go in any direction they want. They are very flexible in this regard. And I think the way they’ve chosen to explore that universe is pure brilliance because it totally broken rank from all the other video games from the nineties. It was perplexing because I couldn’t figure out what the overall story was. But I love it because it’s basically the same story every time with different characters and different situations, yet specific elements are held to be the same, so it feels like the same myth. Sometimes the entire world is flooded, sometimes it’s not. But there’s always a master sword, a triforce and a hero of time.

Differential Style and Orthogonality

Speaking of breaking rank, this brings me to another point: how does an artist’s work fit in with other art at the time? This matters more at the time a piece of art was created and will always be relevant to some extent, but that relevance fades away, leaving the true spirit of the art. Some of the best art is orthogonal to current trends. That is, the art understood what was happening at the time, but its message was completely different in some way. Or delivered in a completely different way.

For the mathematically uninitiated, orthogonality is like trying to plot something on an X & Y axis, yet completely missing the point in some way because the data needs to be visualized on the Z axis to be fully understood. That’s what it means for some relationship to be orthogonal: it’s “statistically independent.” And technically, it is the concept of perpendicularity extended to more than 2 dimensions.

So if you are always judging art by its relationship to other current pieces – which is important, don’t get me wrong – then you are probably missing the point. There is no maximally best way of looking at art, of course. But you can usually identify a great piece of art when it prompts you to remark “wow, this is so different from everything else right now.” That’s a bit self-contradictory because I’ve just said it’s best to judge art for the piece of art itself, not the artist and not the art trend. Still, in order to really recognize how something is different from an artists work, you have to look at that artist’s other pieces. To really recognize a piece of art that breaks trends or breaks some other deeply established concept, you have to know how that art differs from other pieces of art. So in that regard, to judge something for itself requires judging it in context of everything else. To some reasonable degree of course; the best way to look at art critically is to not look at it critically at all.

Gargantua and Pantagruel

But my point is: this concept of style where the artist or author stands against the flowing currents of recent trends, that is an element of style in itself. And often, it’s a very brave one.

Cohesive Style

When you apply style to a work, which kind you apply and how much should seem uniformly embedded in the work, instead of a late idea or something that requires a ton of edits and reworks. Or it should at least seem like style that was conscientiously applied and for good reason. There is a spectrum to the quantity and type of style applied to a work. There is a moreso “major” application of a type of style where that style permeates the work. And there are more “minor” applications of style, which might be more a result of the period of time the work was created than a result of the artist’s intent.

When Style Fuels Artistry

But the best kind of work: you’ll notice something. The style the writer or director pursued feeds back into the work, somehow. Maybe it was this author’s distinctive style or perhaps a style that embodies their philosophy, but if fuels the artistic merit of the work. Nowhere is this more perfectly executed, I think, than in Birdman. In this movie, the style of filming is so perfectly reflected back into the nature of its artistic statements.

Birdman

The one-shot take in birdman isn’t just an technological accomplishment. It’s not just a novelty or gimmick for the film. This is a spectacular example of the use of style to ad depth to the work. The one-shot view highlights the differences between the nature of acting for cinema and for theatre. In a movie about theature. But it doesn’t end there.

This is a movie that makes powerful statements about life & death, about an actor’s failing career and his attempt at a comeback. His career is totally controlled by other people’s perceptions of him. The way they look at him and paint him determines his available opportunities and I’ve been stuck in that same exact spot, time and time again. It’s his attempt to break the mold that his previous work forced him into. And, like Hamilton, he’s got one shot to do it. This is his chance. That is it. It’s high stakes.

The one-shot take revisits some of the same scenes and situations in the play, from rehersal to showtime. This is a statement about the nature of life itself. How often do we find ourselves revisiting the same problems in life? I know I have several times. It’s like a video game and here I am on the same level again. Life is asking me to evolve or restart at the last checkpoint.

Some Spoilers Below

Birdman shifts from the mundane life of an actor trying to regain control of his career to his epic, surreal dreamlike fantasies, where he asserts control over reality by defying its rules. In most film, there’s a sharp, visual break between a scene that is reality and fantasy. Because there’s no such break in birdman, this makes it very difficult for me to understand where reality begins and fantasy ends. This makes the nature of the film difficult to pin down, as no one interpretation of it really fits. Did he die, in the end? Was the ending, was his comeback a fantasy? I don’t know. It’s a powerful statement about suicide, in that again, you only have one shot at life. If he did die, as the film allows us to briefly believe, then he never could have enjoyed the comeback.

Also, the film explores how an artist or actor presents themselves to the world by contrasting the world backstage with the visual imagery of the audience. This divide is emphasized in the marching band scene, which is presented to us the unfortunate accident of a nerve-wrecked actor who bums a cigarette to calm his nerves before that final scene. And he’s nearly stripped naked in the middle of Times Square, where he’s dodging in and out of a marching band as he scrambles to return to the theatre. There couldn’t be more perfect symbolism. He defies the expectation of the audience of the play and the film by winging it back on stage. The actors in the play didn’t see it coming either. He returns to the stage from practically left field, but the character on stage is not an actor. Instead he bears his true self in front of everyone, in what is perhaps a fatal mistake.

And, amoung the points I think the film tries to make, is that such a tightly constraining set of habits for one’s personal life is destructive. That, by never bearing his soul to anyone and restricted by being defined by others, he had found himself cornered. If only he could have show his true self to others sooner, but if others weren’t misunderstanding him through their distorted perspective, then his guard was up, especially when the stakes were high. And we, as the audience of the film get to see what his life would have been like, were he not to have died, which is a brave statement on suicide, I think. Because wouldn’t we like to see a reality where he struggled and succeeded? I don’t believe that’s what “really happened.”

And, so I think the point of the film is that we should be a little less guarded. We should be more willing to show our true selves. We need to cry out when we need help, because our lifes get further contorted. It shouldn’t be difficult for us to do this in our society. It’s hard enough.

Birdman’s “Times Square” Scene

Jackie Brown

This is another great movie and, even though it’s one of his earlier films, I think exemplifies Quentin Tarantino’s style. What I noticed was that, it was everything onscreen was necessary for the film to say exactly what it was trying to say. And it was projected in just the right perspective. Everything that was there was needed in order to develop the characters. It manages to funnel the audience through a very consistent experience, I think. And it does so by tightly controlling the composition of the scenes and the presentation/order of the scenes.

And by doing this, Tarantino is creating a consistent experience amoung his audience, which is very difficult to do. People have very diverse backgrounds and when you’re directing, you have to understand how diverse audiences are going to respond to specific scenes. How is a scene or character is going to make someone feel? If a viewer had one type of response, how would they feel about this plot/character development? Would that compel them to enjoy that moment?

Infinite Jest

This is a book I barely started, so I can’t say too much. I know that the book is written out of order, using the distorted ordinality I referenced above. I’m sure there’s a more appropriate term for this. Even still, the stories that are included are from various characters viewpoints and are eventually woven together. This is a book I’d like to read, but I don’t read as much as I should.

The Title for Infinite Jest Comes from Hamlet

Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio: a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy: he hath borne me on his back a thousand times; and now, how abhorred in my imagination it is!

On the Wikipedia page, it’s noted that David Foster Wallace mentions that “the answers all [exist], but just past the last page.”

The Crying of Lot 49

Another book I need to finish, but so far I’ve noticed that the use of language is remarkable, as are the allusions to other pieces of art. The novel’s only some 150 pages long, but I feel like I need to research all the symbolism as I’m reading it or understanding the novel is hopeless.

On the Road

This novel set the tone for the sixties. One of my favorite books, it was written by Kerouac in the span of three weeks. On a road trip. This novel was written at just the right, spectacular moment of American history, when it had just become possible and economically feasilbe for the average American to travel the continent. This novel embodies the spirit of the impetous road trip, extemporaneously declared by the drunken ramblings of the night before, yet decisively acted on to lead youth on a improvised journey of serindipitous discovery. I love it.

The economic conditions of the late fifties and the sixties permitted this exhilirating exploration of American and the ensuing cultural transformation. The stage had been set and that generation lived out adventures that will remain forever unparalleled. When I remember that we can never again return to that moment, I cry a little bit. Where we are going is just as great and I wish we could return America to such simpler times.

But again, On the Road? Artistic treasure. The style, the action of the writing, everything feeds into it’s own message. And from it, the American legend of Neal Cassidy was born.

Canterbury Tales

This is a collection of stories from the 14th and 15th centuries from Geoffrey Chaucer. Each story is told by a pilgrim on their way to Canterbury from London. The Miller’s Tale is particularly amusing. The pilgrims are from various walks of life and this gives us a good idea of what 14th century life was like in England as well as an idea of what these people might have wanted life to be like.

But this collection of stories is a mechanic used over and over again throughout history. Sin City, the graphic novel and the film, uses it and weaves together a great story. The anime Death Parade also uses this technique to explore the lives of people in their most final moments.

Ghost in the Shell

I recently watched a critique on Ghost in the Shell that discussed the importance of a few minutes of the film with wide shots from different angles and variously sized viewing frustums. Looking at the animation in the footage, some of this was pretty expensive to create. There’s a lot of motion and a ton of effort went into these scenes.

NerdWriter1, who has some other great analyses, highlights the importance of these scenes for establishing a connection to this futuristic world. He notes that these scenes through time out the window in favor for focusing on space. He draws some parallels to the difference between japanese manga and american comics. In particular, he notes that action progresses differently between frames in manga, where there is a bit more focus on frames that only depict the world. He then argues that this is connected to connecting the viewer to the source and sense of identity that these inhabitants of the future experience.

The relationship of identity in a world of constant technological evolution is is paramount for us to understand. This is something society needs to explore and understand before it happens. It’s important theme of the series, which is a frighteningly accurate depiction of tech in the future. And here, the usage of style in composition feeds back into the artistic intent of this series, though not nearly as meta as with Birdman.

My Own Style

I haven’t been writing for long. I have some great ideas. There’s a ton of topics I could write on for non-fiction and I have a few good fiction ideas as well. I have some specific ideas for a world I want to create, but I’m not sure what medium is best. I think video games or VR might be best. But I need to work a lot on style. I’d hate to piss away some of this content by trying to make it the first thing I tackle with my writing.

Similar to how bright colors and intense patterns could detract from the message in a painting, your style could detract from your story, so it needs to be tactfully applied. In my own non-fiction articles on te.xel.io, I choose to be conversational because this is my writing and my message. I am not writing because I want someone to read it. Often my topics and ideas are overly complicated. I discussed category theory in this blog post, for example. I write about too many topics and my posts are too long! A marketing professional would find it quite a challenge to promote my blog in its existing form. I’ve been directly told and indirectly hinted that my content is “too complicated” and that it’s just “way too long” and “way too many words.” HAHAHAHA LMAO!!

The jokes on you. this is my writing and I am writing for myself. I’ll be damned if I disappear without having ever written down my thoughts. And no, I do not want to limit myself chasing short-term goals like increased likes and more retweets and more shares. My blog is not a growth hack. To me, there could be no bigger mistake than changing the nature of my message by limiting the scope and especially the length of my posts to hope that someone shares it. I do not care. I’m looking at the analytics and people are reading my stuff. People are finishing these long-winded, complicated posts.

At the same time, I need to work on improving my style. I want my content to be well organized and I want my message to be focused. Like I noted earlier, revisiting my own writing and imagining it through the eyes of someone else has motivated me to work on my style.

Style Experimentation

So if style is so important for conveying a message and especially for making your work stand out, how do you improve it? Reading is a good start, especially when you are constantly evaluating an authors message and constrasting it with their delivery, while applying that to the context of your own writing, ideas and delivery.

Another good place is seeking creative writing projects. This is a good way to challenge yourself to write a short story or essay, while consciously employing an unfamiliar style. To do this, you have to be aware of your options. I’ve learned that the best dancer can dance with any style, the best actor can act with any style and the best writer can write with any style. That is, they are experts, not by mastery of their own style, but by understanding all styles and cultivating a familiarity with all of them. It’s not crucial to be a master of everything. If we all tried to be the best at everything, we ought to never bother at all. But by at least understanding the innate nature of all kind of things, we can reapply what we learn from one area to another.

And the most important thing to remember is that the most proficient experts in any given field are not limited by their options! If you find yourself bested in some arena of skill, you wouldn’t want it to happen because you ran out of options, would you? Everyone needs to be well rounded, but the very root of all strategy is drawn from having options. From maintaining flexibility. This is a lesson on the nature of strategy itself, formiing it’s core, that can be applied to any game, any field, any industry, anything.

Because writing involves communication of a message about people, then wouldn’t it be best to know people? This is another skill that I feel fairly proficient with, yet one that I badly need to work on. Being an outsider, I have a completely different perspective on people. Being a perfectionist, I feel compelled to keep trying until I find the piece of knowledge I’m searching for.

Part Two - Specific Themes

In the next part, I’m going to list some specific themes I’d like to write about. Some of these are quite depressing, but I feel like life has blessed me with a wide variety of experience, people and places. I’d always love to travel more though.

These themes include ideas on betrayal, compassion, deception, paradox, fate, fame, war, art, wisdom, idealism, mortality, memory, freedom, salvation, philosophy, history, self-discovery, power, misunderstanding, confusion, temptation, and fear.

The majority of these themes I wrote down in just one night. I knew the story I wanted to tell and the lessons I’d learned, but I couldn’t even begin. So instead, I thought to write down all the themes I wanted to write about.