Streaming video transformed the internet in the past decade. So, for VR, what’s the equivalent of video and, in particular, streaming video?

So I watched this video on composition in storytelling, which discussed how directors arrange visual elements for shots. And this sparked my curiosity on several tangents related to the subject, including architecture and VR. Specifically, I want to know how film composition will change for virtual reality.

I enjoy digging into the process of creating something, whether it’s film, art, shoes, business, technology, whatever. I can’t really help it. I have to think about the process used to create that product or piece of art. Whenever I see an ad, I have to think about the marketing strategy, branding and business model, even if the business is boring or obscure. For many businesses, it’s easy to imagine and describe the processes and kinds of roles necessary.

Since film is an industry with a myriad of industries as dependencies, thinking about film production usually kicks off more introspection than is usual for me. For example, I was watching “Clockwork Orange” recently. There was a showing at the Grandin Theater and it was amazing to see this film for the first time in theaters. This movie sparks and drives an internal dialogue in the audience about censorship, obscenity, the role of constraint and morality in society. But also it has a particular style of cinematography, including a perculiar approach to mise en scene. This got me thinking a lot about how the director sourced locations for these shots, since there seems to be subtle iconography in some of these shots, which add to the depth of the film’s overall message.

So, what is the process used to source these shots? And why does it seem that this style of mise en film is absent from most movies today? It seems like it would be difficult and time-intensive to arrange these shots. And i posit that it’s because, unless used properly, it would usually detract from the film. Most films that have the mass-appeal to rake in revenue aren’t artistic and they just don’t need this technique. Focus on this technique pays off for some films and some audiences, but not others. It really depends on your market.

A Mathematic Basis for Mise en Scene

So, what is mise en scene? It’s a term in composition that refers to how the set, actors and cameras coordinate in order to compose the the visual arrangement of elements on screen. It also applies to theater, in which case multiple perspectives of the audience need to be taken into account. This is why mise en scene in VR will be closer to that of theater, rather than that of film. In film, you end up with having basically composed one moving 2D representation. Through this, the audience experiences your vision and derives your message.

However, people are different and, given the same static 2D image, they will observe different things. Not only will they make different observations, they will look at entirely different parts of the image. That’s just for a static 2D image.

So what are director’s trying to acheive with mise en scene? What are they trying to optimize? Having studied a bit of neuromarketing - it’s neuroscience! - here’s the thought that should blow your mind, as I’m taking something typically considered right-brain and bringing full-circle to the more analytic left-brain. I propose that:

By carefully controlling the arrangement of visual elements, the director is trying control the probability distribution, over time, of categorized sets of viewers. This is in an effort to orchestrate the experience of diverse categories of audience members.

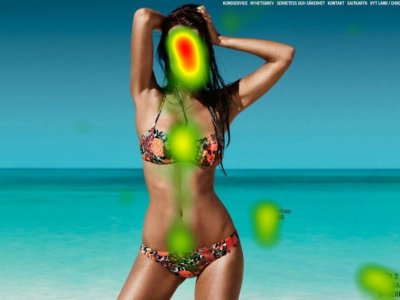

Sometimes, a picture is worth a thousand words. So here you go. This is a probability distribution representing where people look in an image.

See? Probability Distribution:

Made You Look!

This is one of the most fundamental elements of composition in film. If you understand what drives people to look at something, you can set them up to be more likely to pay attention to the right things. And in such a controversial film as A Clockwork Orange, with a diverse set of viewers, many of whom are disgusted at what is happening on screen, then utilizing mise en scene is critical in coordinating their experience. Many of these viewers would otherwise be reviling in disgust and looking away, completely missing some critical aspect of your message. Imagine if someone watched the first 30 minutes of this film and left. Being able to anticipate the visual reaction of homogenous set of viewers is hard. Being able to control the experiences of a diverse audience is masterful.

As stated in the video at the top of the article, Alfred Hitchcock once famously stated that the size of an object on screen should reflect its importance to the film. And why is that? Circling back to my statement that a director is trying to control the likelyhood of a viewer paying attention to the right things, then by increasing the size of someone on screen, then it makes a few things more likely. First, it becomes more likely that someone would begin to look at that object and continue to look at it. Second, it emphasizes details in that object. Third, in some viewers with a critical mind, this may cause them to reflect on the object’s size in relation to other on screen objects. But, like i said, your audience is diverse and you can’t count on all people to understand such critical facets of film.

Other factors you can use to influence a viewers attention include such visual hacks as contrast, focus, blur, color and especially motion. To understand how to apply these visual hacks, you really need to understand what drives attention in the human mind, as well as how we process visual information. These visual hacks can also detract. This is why mugging is so annoying. Mugging is when an actor purposely diverts attention, typically utilizing motion. People can only pay attention to one thing. For an actor with a small part, mugging can be tempting because they can try to get a bit more attention on screen or whatever. Fortunately, everyone knows this trick. Actually, your goal is to play the viewers attention to where it is intended. Do this and you’ll be far better off.

Great, I’ve digressed into offering my amateur take.

Composition and Architecture

I will get to VR, but first, I’ll take a detour. Logistics. That’s the dimension that I find so fascinating about so many subjects that others seem to miss. I like to deconstruct the topic I’m assessing by expounding on the logistic processes required. So, in this case, I’m thinking about how Stanley Kubrick sourced the locations for his shots. Obviously, the guy read the book A Clockwork Orange and obviously, he studied the work to understand what it meant and what it could mean.

How do you go from that starting point to having a fully fledged vision for a film that will spend eternity on most top 100 lists?

Not actually going to attempt to answer this question. What’s the process used to enumerate and evaluate locations for a movie like this? I’m sure there’s a storyboard involved early on, but the location will significantly change what can be planned in a storyboard. The location itself creates constraints on camera shots that can be used.

In the video that sparked this blog post, there was a particularly good example of a shot at 12:30 that contrasts the sizes of two characters, disrupting the visual balance of the image. With the imbalanced shot in this example, the point is to convey a lack of control for one character and a sense of conflict between them.

However, in order to set up this shot in particular, the layout and floor plan of the house itself was important. A similar shot might be constructed in any house, but the layout enabled the cameras to be positioned so that the size of the characters on screen would be in line with the tone of the events onscreen.

Sourcing Locations and Cyclical Iteration

So, sourcing locations for film seems to be critical for mise en scene. There are certain aspects of the story, the plot and dynamics of the characters that you want to convey through image composition. The director needs to decide what to express via image composition and mise en scene, when first storyboarding.

This planning in storyboarding likely happens at the same time locations are being identified. However, knowing what kind of shots you want to frame for individual scenes is crucial in deciding locations for these scenes.

And so there’s a bit of a circular dependency there, which is similar to one that happens when producing a song that features lyrics. Do you construct the beat first? And overlay the lyrics? Or do you write the lyrics first and then write the beat to emphasize the lyrical delivery? The answer is that you do both, though a few cyclical iterations. You develop a bit on the beat, maybe that inspires some lyrics, that flow to that beat in particular. The lyrics you’re developing fit the beat your working on and that’s crucial. Then once you’ve finished the lyrics, you rearrange sections of the beat to match the lyrical delivery, which takes a lot of studio time. If you’re just working with a track that bought rights for via some producer you don’t know, you probably can’t really rearrange parts of the beat. That’s shit by the way, especially if it means you can’t master the track that you’re rapping over.

But cyclically iterating on location and image composition in film can be incredibly expensive, especially if you need to travel to distant locations to evaluate them and plan shots. And this is a very complicated optimization problem, which is why it’s interesting to me. It is more convoluted if you’re evaluating a location that is used for multiple scenes or for a majority of film content. That location needs to be capable of providing a variety of scenarios that provide possibilities for applying compositional techniques, while remaining visually compelling.

And so, when storyboarding, I’m guessing that many shots can be planned in a generic manner. The “Composition in Storytelling” video mentions composition templates. They are invaluable in reducing the complexity of this problem. These can be extrapolated from existing works. Compositional templates can be employed in a storyboard and are then easily be modified to fit a location’s constraints. For example, the order and angle of camera shots could be generically planned out for a scene, then slightly adapted once the location has be set. However, being able to think about this before choosing the location is invaluable, logistically.

And I haven’t even touched on negotiating the legal rights to use a particular location. I can only imagine the work that went into locking down Times Square for Vanilla Sky. I’ve had that dream before. Swear to God. Scouts honor.

Idea: an algorithm for analyzing building layouts to determine composition possibilities would be useful in narrowing down a list of locations.

Buildings with unique architecture are great locations for creating visually striking imagery. Yet when such iconic locations have been used in such a way that contributes to mise en scene, this reduces the likelihood that such a building would be chosen again. This mostly only applies when the film is very popular or critically acclaimed and the imagery created is unmistakable.

However, on the other hand, there are some locations that I’ve seen crop up on screen time after time. In particular, there’s a skating rink in LA that’s used for most shots of roller skating that appear in movies and TV for the past few decades. So besides its location in LA, what makes this rink a good location for film?

Are there some buildings like this which were design, at least in some part, with film composition in mind? If so, this is likely a phenomenon confined to LA, but to what extent would architects design floor plans with this in mind? Have people studied floor plans and schematics used for critically acclaimed films? Or at least studied floor plans to methodically determine what offers the best shots?

It seems that film does affect architecture in LA, at least at a macro level. Based on how spread out LA is, it seems like the development of LA was controlled and restricted in the early and mid-20th century through the implementation of building codes. Otherwise, IMO there would be more urban centers.

Composition in Computer Generated Works

Because limitations seem to enhance creativity, Pixar would have a much more complex problem in designing the composition for shots. While you’re not restricted by the constraints of a location, designing a scene for computer generated movies involves adding in tons of details.

Changes to these scenes would be expensive in terms of time. So when these computer generated scenes are designed, these general image composition rules are likely taken into account and composition templates are employed. The storyboards are constructed around rough sketches of scenes and minor details are added later on. If high detail is added early on, this significantly increases render times and unnecessarily lengthens the feedback loop.

How Does Image Composition Change for 3D Movies?

3D cameras and 3D movies offer a plethora of interesting methods that obliterate subtle constraints of film. For example, mirrors are a serious problem in scene design and restrict camera placement. It’s not a problem with 3D movies though. This is just one example of constraints of 3D film that are just non-existent in 3D. However, these new techniques require equipment, planning and time, which complicate the logistic process of producing scenes.

3D also transends some location-based limitations. You can overwrite any sections of the scene by modeling the scene in 3D. So if the location for a scene has a visual element that detracts from the composition, you can remove it. Or extend it. Or modify it.

There are also tools with 3D film that enable you to alter visual expression of objects in frame. For example, if you’ve read in a 3D mesh that represents the structure of a 3D object, you can easily manipulate those objects in 3D. A great example of this is lighting. With 3D film, you can alter the lighting of objects. You can add lighting for specific objects that isn’t cast on others, like you’re Michelangelo. This creates unique effects on mise en scene, focusing your viewers attention on elements that confuse their subconscious mind with impossible lighting, attracting their attention.

Additionally, you can control the perspective and viewing frustum at render time, applying different perspective parameters to various objects. Again, creating slight distortion that a viewer’s mind knows to be impossible, causing their attention to be directed in an unconscious manner. It’s about breaking the mind’s model of reality, forcing the subconscious to reevaluate something that seems so real in all but one or two dimensions. And yet the experience clearly violates some constraint of the mind’s model of reality. This drives a phenomenon known as a schema violation, which has been extensively studied in relation to intelligence.

Idea: there is no reason why 3D film must be digital first. Creating an analog 3D camera should be possible. Although in most cases, the recording would be converted into digital and combined with digital elements at some point. But there’s no reason a 3D movie could not be produced analog all the way through. Doing so would require specialized cameras.

VR x Streaming Video

Ahhh finally, we’ve arrived. Virtual Reality. How do the rules of composition change for VR? This is a difficult question because we still don’t know how VR will develop as a medium of expression. Obviously 3D movies will take off on VR, but IMO that detached experience might be a bit jarring to a viewer. And there’s the problem of sharing the experience of watching a 3D movie in VR. This is a software problem that’s going to present the consumer with lots of unwanted complexity.

I want to repeat the question I stated at the beginning of the article:

Streaming video transformed the internet in the past decade. So, for VR, what’s the equivalent of video and, in particular, streaming video?

This question allows me to think about VR in such a different way because I feel like there is something we are missing about it. We’re defining VR based on our notions of film and video games today. But IMO, the general public’s perception of VR today is wildly distorted. So much is just not feasible because of constraints imposed by UI/UX, cost, hardware and software. But the business, hardware and software challenges faced by VR/AR is addressed in a pending article.

I personally think that the lack of constraint in VR will prevent the development of one universal medium. That is, there may be no development of an equivalent like film, which is a 2D medium that has clearly stated and universally adopted standards describing it’s ratio and framerate. Because of the divergent nature of the types of experience offered by VR, it doesn’t seem like one of these experience types will establish itself as the universal.

This will certainly be true until 2020. Given time, if there is some universal medium for the expression of art and experiences that emerges, it should become obvious by 2020. We would certainly be well-rewarded by studying the evolution of cinema and video and the beginning of the 20th century. In particular, looking at unsuccessful offshoots in this time: what experimental techniques did people attempt that failed and why?

How Does Image Composition Change for VR?

If the point of mise en scene in 2D is to control the probability distribution of your audience, how do you achieve the same objective in VR, especially if you can’t control the perspective and orientation of the audience. This overwhelming complexity of the VR medium, does this lack of limitation actually limit the capacity of film in the VR medium to convey a consistent message to viewers? And how does the convoluted nature of a medium of the future affect it’s consumer adoption and rate of adoption?

Or does the complexity only seem overwhelming because I’m tightly coupling 360 VR video to film? Perhaps this complexity will be reduced by the exploration of pioneering artists that discover new forms of expression and new composition templating techniques.

This is what excites me about VR. It’s new. It’s unexplored. There are no rules and it’s up to someone to discover those rules and write them. This is a huge opportunity for someone to make their mark. Realizing that this kind of opportunity exists and that basically no one else can see it excites me in a very primal, almost sexual way.

So, for 360 3D VR video, as a director, how do you control the experience of your audience, especially if you can’t count on their orientation and perspective? As a viewer, how does this added freedom to look around affect your understanding and feedback from viewing a static experience. It seems like it’d be strange to view a static 360 video experience while being able to move around.

An analogy can really help to ground the exploration of an unfamiliar subject. The cinematography for 360 VR Video is to that of video as cinematography of video is to photography. Whereas photography is fixed in time and lacks motion, cinematography needs to take these into account, although photography technically does subtly deal with motion. Going from 2D video to 360 VR Video similarly requires adding the ‘dimension’ of the viewer’s orientation. The viewer’s capacity to move adds another dimension to the medium.

A Statistical Model for Directing Focus

So in order to understand how controlling the probability distribution of the focus of our many viewers aids in crafting an experience, it may be of benefit to return to the mathematics-inspired analogies. It may seem Daedalian, I know. I hope you’ll excuse my tendency to reach for math and other abstract, hard to understand concepts, but doing so really does help me reason about this stuff.

So. In general, how does added dimensionality affect a problem? Personally, I need more understanding to answer this question, especially if I were to apply it to the problem at hand. However, I can say that increased dimensionality can complicate a problem space, but also simplify it as well. Here, dimensionality doesn’t refer to typical Euclidean dimensions of space, but to the range of options available to the artists. It’s instead a widely increased feature-space.

The reason I’m mentioning math here is because it’s a means of methodically developing knowledge of VR as a medium. If you understand how to combinate through the various permutations of VR as a medium and comprehend how each one functionally differs, then you can foresee how each would be useful as a medium of expression. Math really isn’t the only way to come to understand this and it’s too esoteric for most, but it works for me.

But think about it: there’s lots of opportunities here and not just for the artist. If you understand how these variations of VR expression will develop and how consumers will approach the industry, the you can anticipate demand for products. Step 3: Profit

Differentiation in VR Media

All content in VR will be stereoscopic 3D. The forms of media available in VR can be differentiated by the degree of freedom available to the viewer, player or user. There will be uniform, serial experiences, like a film, where the viewer streams the exact same content as someone else. But the degree of freedom determines how the audience members could perceive it differently.

Another degree of freedom can be added to a serial experience and that’s position. The viewer can move around and experience the work from various positions. IMO, I just don’t think the benefits outweigh the increased complexity and diluted ‘bandwidth’ of either 360 3D video and video where the viewer controls the position.

And a final degree of freedom can be added, by removing the temporal requirement of serial media. By serial, I mean like a type of medium where the content is streamed, but each viewer receives exactly the same content. Another form of medium can be created, which is like a cross between a video game and a movie. It’s like an event-driven experience, where you are allowed to proceed through the story at your own pace. The characters on screen react to events you trigger, though you may or may not be part of the story or acknowledged by characters on screen.

This seems to resolve some of the problems described above, but introduces a major problem: how would you experience this with a friend. Though, I suppose you could configure the experience to be streamed to a group, but it still raises a lot of questions. Among them: why wouldn’t you just play a video game?

Yet, I still don’t think I’ve described a medium which would become the streaming media of VR. And that’s because I believe that will be moreso part of AR and that our preconceived notion of VR is more of a red herring.

Guiding the Experience of Your Audience

So, what tools are available to reduce the complexity of VR? Most of the techniques used to guide the audience’s experience here will be based on anticipating their reaction to events onscreen, then guiding it towards the next intended point of focus, using strong sensory signals.

3D audio is a good example of a technique that can help direct the focus of your audience. 3D microphones have recently been developed, specifically to capture audio for Oculus Rift and 360 3D movies. This kind of audio is going to require complicated new software tools as well as new techniques. Using binaural audio cues, one can direct the viewer towards an anticipated focal point.

A 3D Binaural Microphone

Another interesting technique would be to use lots of POV shots in 360 3D video. So, you would switch from character to character, at times, I guess. Actually, the more I write about this, the more limiting it all seems. AR is going to be way more interesting, but much harder to achieve technologically.

The most useful tools for understanding the process for creating the best VR experiences? Data & analytics. Any VR video platform should incorporate data collection to assist in analyzing user response. This will be invaluable in understanding how to create art in VR.

Problems with Composition in VR

It’s difficult to create a consistent experience when your audience is free to move their head around in VR. How do you arrange the scene, to get the perfect shot, if a viewer might not even be looking? More importantly, why would you bother with aspects of mise en scene, if they’re just going to be overlooked? Does that mean that many typical techniques will no longer be utilized?

Some techniques could be proposed to fix aspects of 360 video. You could force the viewpoint to move/snap to a point for important scenes. But IMO, that’s going to feel jarring to the viewer. If you’re going to allow the freedom to look around, then you’re going to have to be more creative than that.

The order of and transition between camera shots will be another problem. With 360 video, how do you resolve where the user is looking when transitioning to the next camera shot? Do you transition to the next scene, but oriented towards where they were looking. Or towards where they should be looking in the next scene, albeit with their head oriented in the previous direction? The latter won’t work at all after multiple scene transitions. The former’s not exactly a solution either, as the director can’t really anticipate where someone would be looking before the transition.

A subtle technique in film is to attract the viewer’s attention to a point, then transition to the next shot, so that their point of focus still remains in the point where they are most likely to look. This is fucking gold in advertising. You can use motion to ensure that, in the next shot, the viewer is looking right at the brand name. You can’t really do this with 360 video.

VR x Theater

Congratulations. You made it. I don’t know how, but here you are.

This is a cross of VR and Theater, as in live theater. This starts out pretty cool, but gets way cooler with the advent of AR, around 2018. Think of a virtual hangout, where you can watch people perform.

Uhh… not Twitch, it’s not Twitch, although they’re perfectly positioned to capitalize on this.

Actors could perform live theater in front of a virtual audience. As a viewer, you could render yourself among a huge audience or just with your friends.

Integration of AR techniques is where this starts to get really awesome. Imagine being in a live Pixar production. The actors could be interacting with motion sensing equipment and perhaps experiencing the VR themselves.

In Summary

What is the universal medium of expression for VR that will be the equivalent of film? Again, what’s the equivalent of streaming video in VR? Both of these are difficult to pin down.

3D video will certainly take off. 360 video might just be more of a feature than a format, assuming your 3D video is rendered for variable perspective. There will undoubtedly be a variety of novel forms of expression through VR, but most will derive their value from novelty.

VR is infinitely more valuable to games and simulations than video. For video, VR complicates way too much. It requires more investment and more process in a film production. There’s already enough of that. IMO, plot, background and characters are the most important aspects of a story. Far more crucial than the video, sound or graphical medium, although they certainly important.